The Women You Didn’t Know Built Hollywood

How women in film went from silent stars, to just silent.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

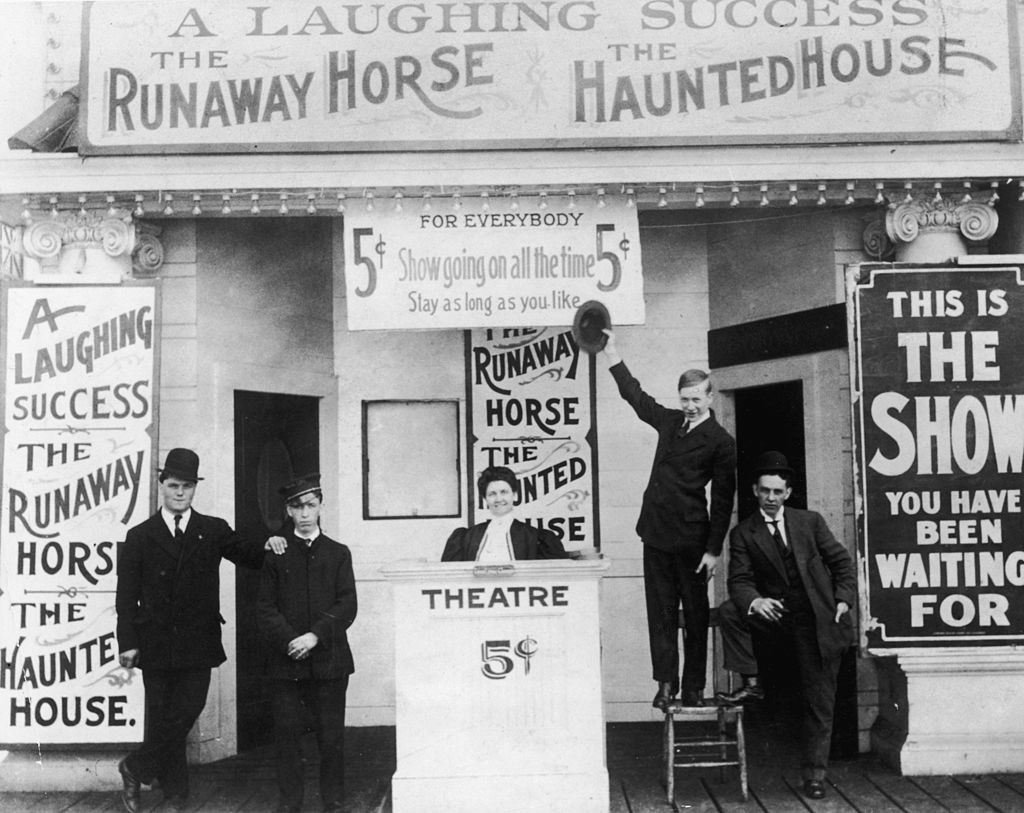

The most exciting, high-tech entertainment money could buy from about 1905 on was the nickelodeon, a small neighborhood theater that ran silent motion picture short films. The nickelodeon craze created a huge demand for one-reel “short” films, necessitating the creation of a massive industry almost overnight.

The work was labor-intensive and arduous, especially after the film had been shot. It took hours or days to “join,” or edit, snippets of film into complete reels. This back-breaking, unglamorous work attracted many young women eager to embark on careers.

“Assembling reels and cutting negatives was tedious work that often fell to young working-class women.”

— Kristen Hatch, Women Film Pioneers Project

In the early days of film, when “woman’s work” had yet to be defined, women did more than just “join.” One 1923 article in Business Woman magazine named 29 different jobs women held, from typist to actress to director. This fluidity made the first Los Angeles studio lots a “laboratory for gender experimentation,” as Mark Cooper put it.

In fact, screenwriting — today dominated by men — was initially thought of as woman’s work, creating opportunities for women to play a crucial role in filmmaking. While actresses were without a doubt bigger stars than men, it’s a little-known fact that women worked behind the camera, too—in fact, many of them were directing pictures. Many women like Marion Leonard, Helen Gardner and Gene Gauntier left their film companies and started their own production houses, alone or with their husbands.

“Star name companies” run by couples bore the female star’s name more often than the man’s. The movie press eagerly championed these companies, and spoke in glowing terms about female contributions to film. Women owned some 40 production companies by 1923.

Naturally, it’s difficult to determine whether the male or female partner wielded the most power, which is one reason the role of women in early film remained unclear for decades.

Another reason was credits, or lack of them. Credits only appeared in the film press and in films themselves around 1911. Shifting job descriptions mean historians must sift through antiquated titles like “picturizer,” “scenarist,” “cutter” and “directrice” to determine who did what. There’s also the fact that less than a quarter of silent-era films have survived.

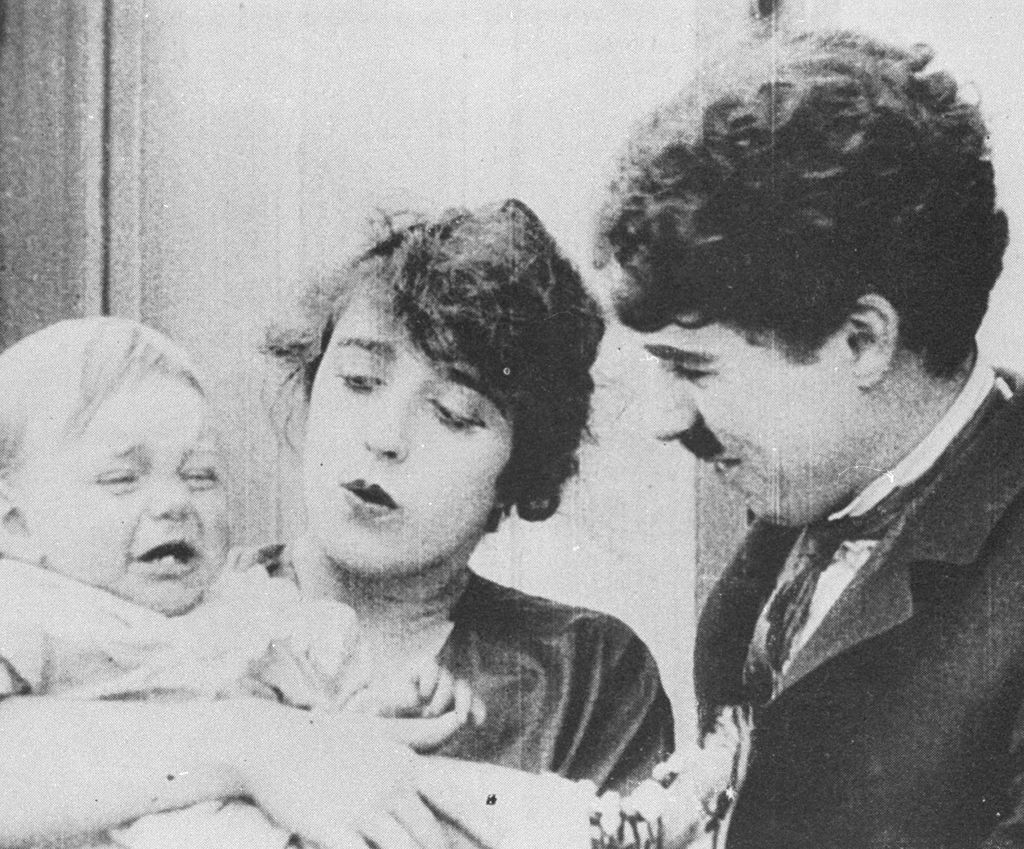

Other times, credit was simply stolen. Comedian Charlie Chaplin infamously titled himself Director on numerous films directed by Mabel Normand, even though she had championed Chaplin when his fledgling career was faltering, and had taught him how to direct!

We now know women did much of the heavy lifting, behind the camera and in front of it — sometimes all at once.

“In addition to playing the principal parts, I also wrote, with the exception of a bare half-dozen, every one of the five hundred or so pictures in which I appeared. I picked locations, supervised sets, passed on tests, co-directed with Sidney Olcott.”

— Actress, producer and director Gene Gauntier in Photoplay, 1924

While the female suffrage movement was on the rise, an unexpectedly small number of women in film drew parallels between their work and the fight for women’s rights. But some, like Beatrice deMille, recognized the larger implications of their work. DeMille, a writer and agent and the mother of motion picture magnates William and Cecil B. DeMille, wrote, “This is the woman’s age. I think it has come to stay. Every relation between the sexes has changed.”

A backlash was coming, however. Movies had become big cash cows, and industry leaders were keen to maximize profit by implementing the innovations in management that swept the business world in the 1920s. The short films that had given many women opportunities began to be replaced by multireel “features.”

“The one- or two-reel short film represented creative opportunity, and if there is a Golden Era of writing, producing, and directing for women in the US industry, it corresponded with the vogue in shorts.”

—Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, “Women Film Pioneers Project”

With the massively higher budgets features involved, large studios had an incentive to stamp out competition from small companies.

A widely read 1924 editorial in Photoplay magazine reversed the tradition of media adoration for female-led production houses, charging that women weren’t efficient, or team players:

“Aligning itself with new principles of management applied to the creative process, the magazine sees women’s independent companies as the ‘bane of the industry,’ because, harkening back to an earlier stage, they threaten to ‘drag film-making back to its days of solitary, suspicious feudal inefficiency.’”

In the most damaging development, First National Exhibitors’ Circuit, the consortium that had supported the star name companies by distributing their films, became a production company itself in 1922. Indie star-producers like Corinne Griffith, who’d left a major studio at the height of her career, received rigid new contracts that “gave her no control over budget, casting, or script, and no profit-sharing,” negating all the benefits of independence in a single stroke.

“Although few recognized it at the time, this was the end of the World War I-era independent movement and the end of the line for female-headed production companies.”

— Karen Mahar, “Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood”

The era of silent short films and star name companies made way for the “studio system,” which centralized and dominated movie production of expensive and more profitable multireels.

Now that working on films was considered “good” work, it became men’s work. With the introduction of sound, female editors — who’d always had a free hand — suddenly faced interference from men in studio effects departments. Entry-level jobs began going to men. In 1940, the Los Angeles Times called “lady film cutters a vanishing profession.”

A few women screenwriters, editors, and of course actresses, continued to drive innovation in an otherwise male Hollywood, but the Golden Age of women in film was over.