The Unknown Journalist Brave Enough To Expose Stalin’s Secrets

Doing the right thing cost him his life.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

The horrors of the Holocaust are well-documented. But there’s an equally horrifying genocide that happened during the 1930s that’s much less well known: Holodomor. This artificial famine — caused by the Russian government from 1932-33 — killed 4-10 million Ukrainian peasant farmers.

The Soviet Union managed to conceal it until the late 80s. But they were almost found out in 1933 by a Welsh journalist named Gareth Jones.

Gareth was born in 1905 in Barry, a town in Wales. His mother had once worked as a children’s tutor in the Ukraine. Her stories about the country inspired in Gareth a love of language and a desire to visit Eastern Europe.

Early on, Gareth displayed a talent for languages. He studied French, Russian and German and soon became fluent in five languages. After graduating, he leveraged his linguistic skills into a career, using them to infiltrate political and diplomatic circles. By the time he turned 25, he had a job serving as foreign policy advisor to former British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

Friendly with Nazis

In the 1930s, Gareth worked as a reporter for the Western Mail, a Welsh newspaper, covering the Nazis’ rise to power and writing favorably about their economic achievements. In his work, Gareth cultivated friendly relationships with Nazis, gaining unprecedented access to high ranking officials. He was present in Leipzig in 1933 when Hitler became chancellor of Germany, and flew alongside him to Frankfurt for Hitler’s first political rally.

Gareth’s ability to network with Nazi leaders raised eyebrows: some voiced concerns that he might be a Nazi sympathizer. However, Gareth also recognized the anti-Semitic sentiments that were at the crux of Nazi policy and predicted the party’s downfall.

‘Famine Gripped Russia, Millions Dying’

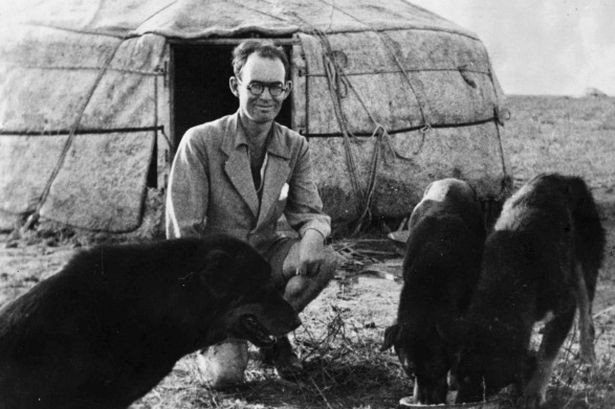

After covering Hitler’s rise to power, Gareth traveled to the Ukraine for a two-month reporting trip. His language skills — coupled with his political credibility — gave him access to politicians and peasants alike.

Gareth’s trip to Eastern Europe came at a terrible time for the region: in 1917, just 16 years earlier, the Bolsheviks had come to power under Vladimir Lenin. They were succeeded by Joseph Stalin who was intent on enacting a “five-year plan” to industrialize Russia. In 1928, Stalin introduced a policy of agricultural collectivization, forcing farmers to give up control of their personal assets and join state-owned factory farms. Russia used the crops from these farms to feed industrial workers living in cities.

This policy resulted in a man-made famine that became known as Holodomor. Stalin purposely targeted ethnically Ukrainian areas and regularly punished successful farmers as well as political and religious leaders by deporting them to remote areas like Siberia or simply executing them. Millions of people perished under Stalin’s draconian policies.

During his time in the Ukraine, Gareth noted the tragic conditions he witnessed. On March 29, 1933 he called a press conference in Berlin to report his findings. The New York Evening Post and the Manchester Guardian published an article he wrote titled “Famine Gripped Russia, Millions Dying.”

Here’s a powerful bit from that story:

“I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying.’ This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, and Central Asia. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.”

Both the Russian government and the mainstream media denounced and attempted to discredit Gareth’s claims. Two days later, Walter Duranty — a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for the New York Times — published an article titled, “Russians Are Hungry But Not Starving.”

“Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda,” he wrote.

Kidnapped by Japanese outlaws

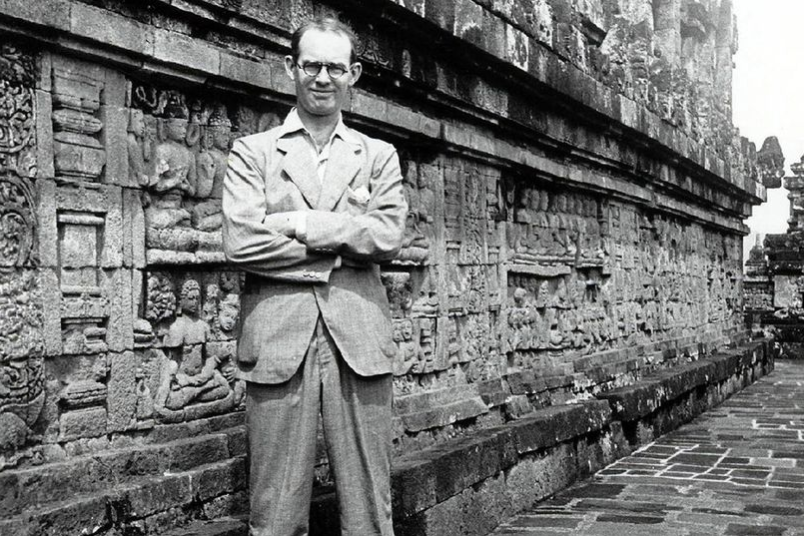

After the publication of his article, Gareth was banned from Russia and relegated to journalistic obscurity. He returned home to Barry to live with his parents and work as a junior reporter for a local outlet. After a few months, he got word that the Japanese had occupied Inner Mongolia. He left with another journalist — a German named Herbert Mueller — to investigate.

While traveling by car in China from Dolonor to Kalgan — a trip of about 160 miles — Japanese bandits kidnapped both journalists. It’s unclear whether the Japanese or the Russian secret police (the NKVD) tipped off the bandits. What we know is that the bandits released Mueller, supposedly in the hopes that he might return with ransom money.

Jones wasn’t so lucky. On August 12, 1935 — the day before what would have been his 30th birthday — the bandits shot and killed him.

George Carey — who directed the 2012 BBC documentary called “Hitler, Stalin and Mr. Jones” — says that investigations into Jones’ death revealed that he may have been set up. A man named Adam Purpis — who said he was a Latvian fur trader — loaned the journalists a car. Purpis was later proven to be an NKVD agent. There is also evidence suggesting that Mueller may have been a Russian agent himself.

Despite Gareth’s brave attempt to share the Ukrainian people’s suffering with the world, the truth about Holodomor did not come out until the late 80s, as the USSR was beginning to fall. In 1991, Ukraine won its independence and in 2006, the Ukrainian parliament decreed that Holodomor was a deliberate act of genocide. (To this day, the US does not officially recognize it as a genocide, choosing instead to call it “a criminal act” of Stalin’s regime.)

In 2008, Ukraine awarded Gareth the Ukrainian Order of Merit for services rendered to the country and its people. The New York Times later denounced Walter Duranty’s reporting on Russia, but the Pulitzer committee never revoked his Pulitzer Prize (they officially declined to do on more than one occasion).

Gareth Jones was likely aware that speaking out against Holodomor might come with severe repercussions. Nevertheless, he persisted — even at the expense of his reputation and his life.